Following on from last week's Viewpoints series where Lara Hanlon, James Delaney and Mel O'Rourke each answered the question, 'So what is design thinking, anyway?', we thought a more in-depth look at design thinking, its origins and its possible future could be pretty useful. Cue Dr. Hilary Kenna, Head of Department of Technology & Psychology, IADT, who has developed a new Postgraduate Certificate in Design Thinking at the college. She provides us with the ultimate primer:

Opportunity

There’s often a palpable sigh from designers when the term ‘Design Thinking’ is mentioned. That’s because they have an inherent scepticism about the current popularisation of a practice they’ve been doing for years. For many, design thinking is intuitive, a daily part of the job of being a designer and it is disgruntling to watch the commodification of this process. While some fear that design thinking could undermine the job of designers, I believe the ground swell of interest in design thinking from other disciplines is actually augmenting the value and importance of design.

A new design literacy is emerging outside the discipline of design that it is facilitating a deeper engagement with design in general. Many sectors – business, finance, technology, health, education – now recognise that design and designers can help to solve really difficult problems and create innovative solutions not thought of before. For designers, design thinking is a help not a hindrance and it is worth understanding what all the fuss is about.

Origins

The origins of ‘design thinking’ is closely aligned with the origins of ‘scientising design’ which according to Nigel Cross, in his book Designerly Ways of Knowing (2006), emerged in the 1920s Constructivist Movement and then became a focus for study in its own right in the 1960s Design Methods Movement in London. However, other early pioneers of design thinking were clearly rooted in the sciences. Herbert Simon (an American political scientist and economist) in his book The Sciences of the Artificial (1969) encompasses theories and methods from cognitive science and cognitive psychology, while Robert Mc Kim (Stanford engineering professor) devised visual thinking methods for design engineering (Mc Kim 1973). Design thinking has also borrowed methods and practices from architecture and urban planning for wider audiences and general education (see Lawson, 1980 and Rowe,1987).

More recently, design thinking has gained traction and popularity via the technology sector, where it has grown up alongside HCI (human computer interaction) – the computer science approach to designing technologies for users. HCI’s quest, within its broader scientific domain, has been to derive empirically driven methods that quantify best practice for designing and testing effective human computer interactions. In HCI, this usually means focusing on the design of the user interface (UI). In the past however, it is clear that the design of computer systems were often difficult to use and lacked aesthetic appeal.

Amongst the early and best-known HCI stalwarts are Stuart Card, Donald Norman, Ben Shneiderman, Bruce Tognazzini and Jakob Neilsen. Their output covers a range of empirical guidelines and principles about user interface design that includes: how to identify a user task and profile user proficiency, a menu of interaction styles, eight golden rules for good user interfaces (Schneiderman), ten usability heuristics (Neilsen Norman Group) and sixteen first principles for designing the user interface (Tognazzini). These methods are commonly taught up and down the labs of many Computer Science degrees around the globe but much less so in design schools.

Donald Norman and others, notably brothers Tom and David Kelley began to undertsand that HCI methods could be applied beyond computing. They adopted a broader ‘human centred-design’ (HCD) or ‘user-centred design’ (UCD) approach that shifted from purely quantifiable methods to include the emotional side of the user’s needs. This new design process with a focus on empathy–that includes the user’s desires, motivation and ability– has evolved into design thinking as we know it today.

Definition

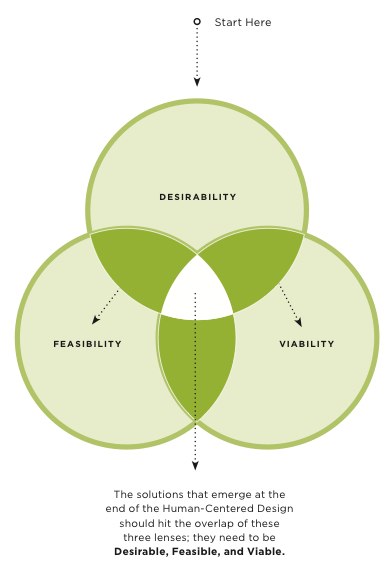

Tim Brown, CEO of IDEO, created the now famous diagram that best summarises how design thinking should bring together what a user needs, wants and desires, with what is technically feasible and economically viable (figure 1).

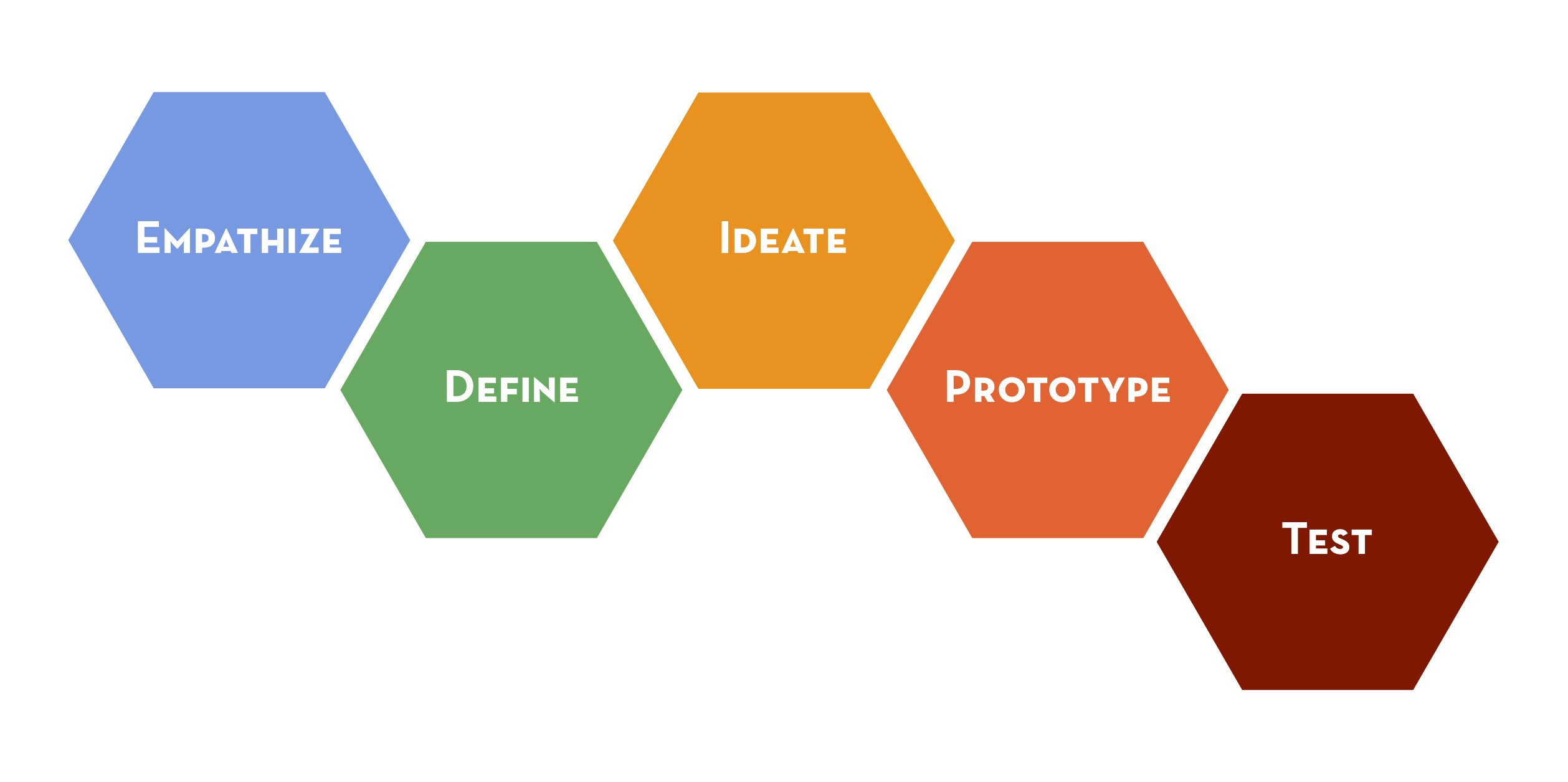

His colleague, David Kelley, founder of IDEO and Professor at the D-School in the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design, Stanford University, is probably best known for developing a user-centred design thinking process that encompasses five stages: empathise, define, ideate, prototype and test (figure 2).

The D-School has spread this method around the world. Other forms of design thinking have also become popularised by the likes of the LUMA Institute, IBM, Ratford University, IIT Institute of Design. However, most variants are essentially the same – proposing an iterative design process that incorporates user-centred research, problem definition, ideation, exploration, prototyping and testing. The distinctive aspects of the design thinking process are its central focus on customer needs and its collaborative nature as a team activity.

Design thinking involves cross-functional teams (not just designers) but also engineers, marketeers, business, finance and sales people, as well as users, customers and other stakeholders. At key stages of the process, these team activities can involve ‘co-design’ or ‘participatory design’ workshops. This process does not disempower designers, but helps to ensure that a problem is examined from multiple perspectives and that nothing is overlooked. When design thinking is done right, it is used for inclusion not consensus building. Practical methodologies may also leverage mind-set change and help with ‘buy-in’ from different stakeholders, but again this doesn’t necessarily mean agreement. It enables the team to identify different directions and rehearse the pros and cons with real customers.

It can help provide ‘proof’ that a chosen direction or approach towards a particular solution is the right one.

Design thinking facilitates rapid prototyping of ideas and testing them with real customers throughout the process of design and development. The ultimate aim is to ensure the solution stays focused on meeting identified goals and hopefully exceeding them by the time of completion.

Currency

Why design thinking has become so relevant and popular now is a question designers often ask. The answer is probably as complex as the ‘messy’ problems that design thinking is being used to tackle and solve. The digital data age we live in is immensely complex and rapid. The speed of change in work, education, social and consumer experiences that are facilitated by access to online information and communication is overwhelming. People can find information about anything from anywhere at any time and share it instantly with their immediate peers or the world at large. We hear daily about the new and emerging technological trends, such as automation, artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things (IoT), blockchain, virtual and augmented reality, that threaten to disrupt our daily lives. Every company, manufacturer and service provider (public and private) is currently trying to find a way to navigate this confusing future technological landscape.

Design thinking has already been used by some of the most successful and innovative companies during the last couple of decades, by pioneers like Apple, IKEA and Lego, and new comers such as Spotify and Airbnb. Traditional sectors of technology, business and finance are now acquiring design thinking capability within their organisations – IBM, Pepsi, Accenture, Deloitte are well publicised examples. Even government departments and public sector organisations are employing ‘design thinking’ tanks in their quest to solve ‘wicked problems’ around global issues of aging population, food shortage, climate change, smart cities and sustainable energy.

Benefits

Design thinking does not replace what designers do and make in creative practice. If anything it strengthens their hand (literally and metaphorically). It moves design to a central position, underlining its importance and impact, aligning all stakeholders involved to work towards achieving the best solution possible. However, there is no denying the tension that exists between creative and scientific perspectives on design. In 1980, Brian Lawson, a professor of architecture conducted an empirical study that examined the difference between scientists’ and designers’ approaches to problem solving. He found scientists solve problems by analysis, while designers solve problems by synthesis. Tim Brown and David Kelley believe that for design thinking both analysis and synthesis are needed. This might also help to explain why creative designers don’t warm to the explicit systemised version of design thinking that IDEO and others have popularised. They perceive it as overly analytical and rational, not fertile ground for fostering creative ideas and lateral approaches.

Nigel Cross and Donald Schön, amongst others (Simon,1969), (Glynn, 1985), (Polanyi 1958) recognise that the distinct value of design is as a practice of making – a constructivist approach to solving ‘messy problems’ through invention (Cross, 2001). This is what makes design as a discipline unique to other fields. According to Schön, designers use implicit, intuitive artistic processes and apply them as an effective means to solve difficult, non-quantifiable problems that could not be arrived at through analytical, logical and scientific means.

Michael Polanyi also refers to this as a ‘logical gap’ that exists between knowledge, and discovery or innovation, which cannot be crossed with factual knowledge, logical reasoning or iterative development of existing concepts. According to Polanyi, a kind of leap or ‘illumination’ is also required so new concepts can be proposed and developed to bridge the ‘logical gap’.

It is … design that has inherited the task of developing the logic of creativity, hypothesis innovation,

or invention that has proved so elusive to the philosophers of science. (Glynn, 1985)

Many scientists and non-designers have also come to believe that a solely analytical approach does not yield innovation. Harvard Professor Clayton Christiansen, a leading expert on disruptive innovation, cautions that a data-driven approach to design is doomed to failure because it tends to be reactive and backward-looking, rather than the forward and speculative thinking needed to solve future problems. Even Donald Norman has shifted from a purely quantitative perspective, as he famously explains in his TED talk on ‘emotional design’, recognising that aesthetics and human desire is as important to design as function and economics.

Truly innovative design can’t depend on what we know – existing pain points for customers, features that competitors don’t have, cheaper versions of an existing product – it has to anticipate what we don’t know in order to imagine and create better experiences, products, services and systems that don’t exist yet. Design thinking can help designers play out future scenarios and test them, but it can’t necessarily make the creative leap to bridge the logical gap to better design.

Future

Design thinking is now bound up with a much larger context, not solely concerned with designed outcomes or artefacts, but as a mind-set, as a process and a set of methods for change and innovation. It is being applied in many different contexts from business and societal problems to large-scale humanitarian issues. It is providing a practical modus operandi to address difficult problems in non-traditional ways.

But design thinking can also be liberating for designers. It can solicit the true views and perspectives of customers, clients, stakeholders so designers don’t have to second guess. Because it involves customers and clients in the design process from the outset, they tend to be more invested and receptive at each stage of the process.

Designers should acknowledge that design thinking is already, and will continue to be, part of their toolset, and now that others outside of their discipline are acquiring this literacy, the conversation and engagement with design will be more fluent and effective and in the future will happen at scale.

–––

References

Christensen, C., (2012), Linked In Lecture Series, How will you measure your life?

Cross, N., (2001), Designerly Ways of Knowing: Design Discipline Versus Design Science, Design Issues, 17, no. 3, pp49-55.

Glynn, D. (1985), Science and Perception as Design, Design Studies 6:3, Elsevier.

Polanyi, M., (1958), The Personal Knowledge – Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

Schön, D., (July 1988), Editorial, Design Studies, Volume 9, Issue 3, Pages 130-132.

Schön, D., (1985), The Design Studio: An Exploration of Its Traditions and Potentials, Intl Specialized Book Service Inc.

McKim R., (1973) Experiences in Visual Thinking

Lawson, B. (1980) How Designers Think

Stanford D.school, (2016), The Design Thinking Playbook. Retrieved from: https://dschool.stanford.edu/resources-collections/browse-all-resources

Brown, T. (2009), Change by Design – How Design Thinking Transforms Organisations and Inspires Innovation, Harper Business, Harper Collins.