Social design also known as ‘design for good’, ‘design for the real-world’ or ‘design for positive-social impact’ is described by Elizabeth Resnick as design made with the primary motivation to promote positive change (Resnick 2019). Within this area designers are often described as ‘agents for change’, ‘citizen-centered’ or ‘socially responsible’. The roots of social design are said to have begun in the 1960s within the writings of Austrian-American designer Victor Papanek, Professor Nigel Whiteley and design historian Victor Margolin. The field has expanded since its beginnings and it’s still evolving. The global network Design for Social Innovation towards Sustainability (DESIS) set up in 2009 by Ezio Manzini now has eighty-six laboratories located in design schools in Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, South America, and Oceania with the goal of promoting design for social innovation in higher education institutions. There are a host of higher education courses in Ireland, the United Kingdom, America, Paris, Italy and Germany, that offer Master’s specifically devoted to design for social impact, such as MA Design for Social Innovation and Sustainable Futures (UAL, UK), Social Design Academy (Eindhoven, NL), Design for Change MA (Edinburgh College of Art, UK), Social Design and Sustainable Innovation Master of Arts (Berlin, DE), Master in Social Innovation for Sustainable Development (Turin, IT) and MFA Design for Social Innovation (NYC, US). Recent contemporary discourse on social design has been shaped by Jan Boelen, artistic director of LUMA and Micheal Kaethler who both teach on the Design Academy Eindhoven Social Design Master’s programme.

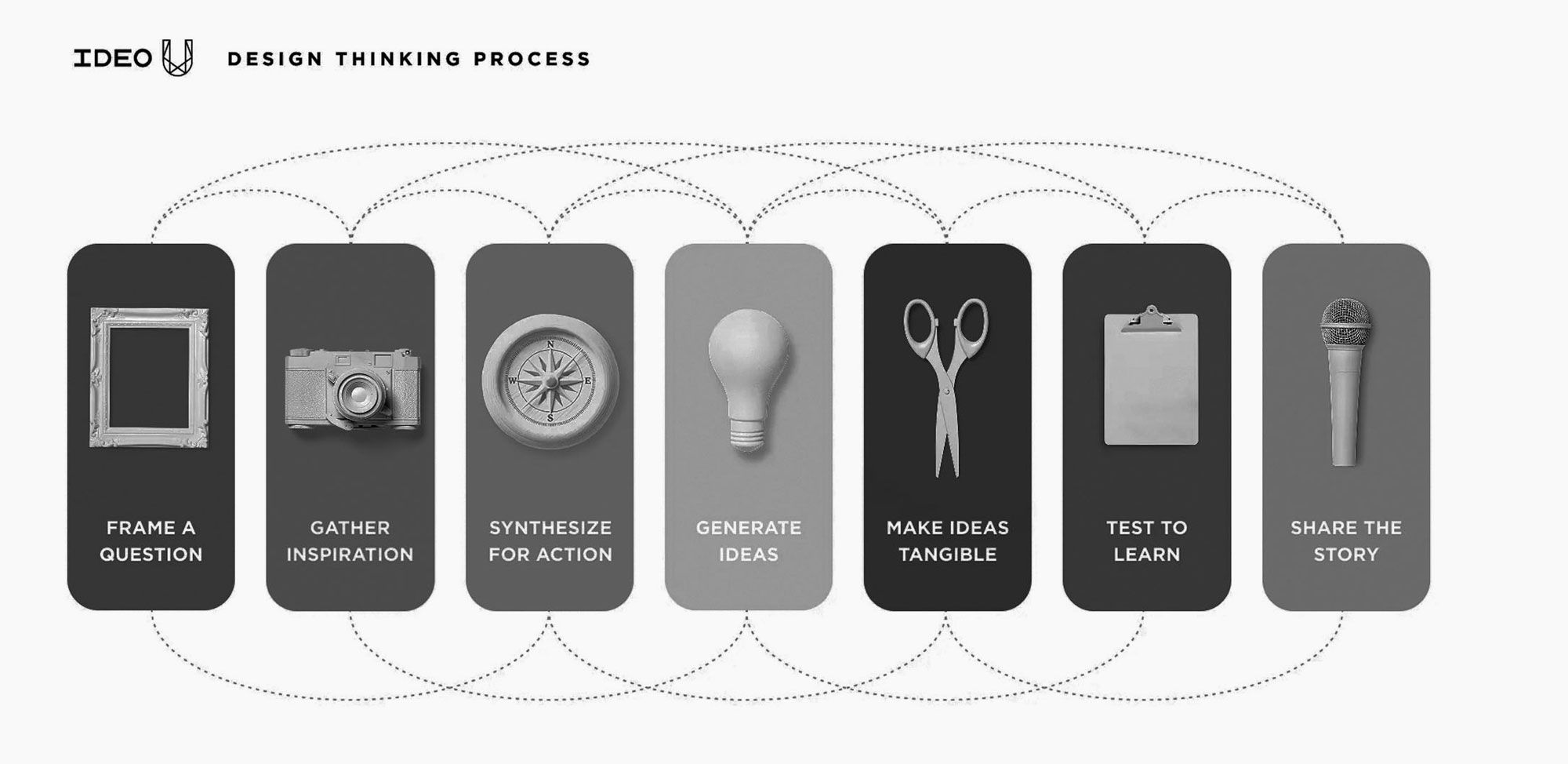

Social design has come under criticism from academics and designers. Described as a short-term sticking plaster to social issues, rather than a long-term solution to root causes of problems. Design Thinking is described as an innovation method, often used within the field for social innovation. It can be traced back centuries but came to prominence when Tim Brown CEO and president of IDEO published an article in Harvard Business Review. Brown suggested that as innovation’s terrain expanded to encompass human-centered processes and services as well as products, designers needed to create ideas rather than simply just dressing them up. Underpinned by corporate solutionism, design thinking is often accused of being a neoliberal design lens (Stern and Siegelbaum 2019). Some might say that design thinking shifts the onus of responsibility away from the state and/or society at large and on to at-risk communities themselves (Cook 2019). A systems thinking approach is often utilised within social design projects with Human-centered design frameworks. Some tools might include things like persona creation, empathy maps, and/or user testing. These methods were seen to shift design as a ‘product’ preoccupied with form and aesthetic value and move towards a more human-centered problem-solving process, that could be utilised in various contexts and provide ‘real-world’ solutions (Brown and Wyatt 2010).

One ‘real-world’ example given in Design Thinking for Social Innovation discusses a case study outside Hyderabad in India. A woman fetches water daily from the always-open local borehole about 300 feet from her home using a 3-gallon plastic container she can carry on her head. It’s not as safe as water from the Naandi Foundation-run community treatment plant, but they still use it, and it periodically makes her family sick. Brown and Wyatt describe how the woman has many reasons not to use the water from the Naandi centre, but they aren’t reasons “one might think”. The centre is within easy walking distance of her home, well known and affordable. Habit isn’t a factor, either. Brown and Wyatt propose that “The designers of the center, however, missed the opportunity to design an even better system because they failed to consider the culture and needs of all of the people living in the community”. They surmise that the Woman is forgoing the safer water because of a series of flaws in the design of the system. Although she can walk to the facility, she can’t carry the 5-gallon jerrican that the facility requires her to use — when filled with water it is simply too heavy, and isn’t designed to be held on her head. The treatment centre also requires them to buy a monthly punch card for 5 gallons a day, far more than they need. “Why would I buy more than I need and waste money?” she asks. Wyatt and Brown conclude that the designers missed the opportunity to design an even better system because they failed to consider the culture and needs of all people living in the community. They go on to say, “that time and again, initiatives falter because they are not based on the client’s or customer’s needs and have not been prototyped to solicit feedback, they may enter with preconceived notions of what the needs and solutions are”. Wyatt and Brown maintain that this flawed approach to design remains the norm in both the business and social sectors.

Charities are businesses, and the social sector does not avoid economic constraints. Social enterprises utilise alternative business models to achieve social missions but issues can arise when designers define problems in isolation. Taking the Naandi case study as an example, instead of describing the “problem” as having no fresh running water at home, or finding a solution to the unsafe local drinking water, the objective becomes: how do we get this woman to buy water from Naandi instead of using the local watering hole? This reframing reduces a complex political public health issue to a question of consumer behaviour, prioritizing market logic over lived realities. The charity sector is a business sector like all other business sectors and to think of charities as inherently good businesses is flawed. This is not to disparage the Naandi centre in any way, whose work is vital, rather the case study highlights how even well-designed interventions may fall short and neglect to consider the bigger political systemic issues and/or complexities that ‘local’ communities might not divulge in interviews or focus groups. One question that must be asked is who are the real beneficiaries from social design solutions. As Cook notes the design thinking methodology within social design relies on turning identified problems into market opportunities.

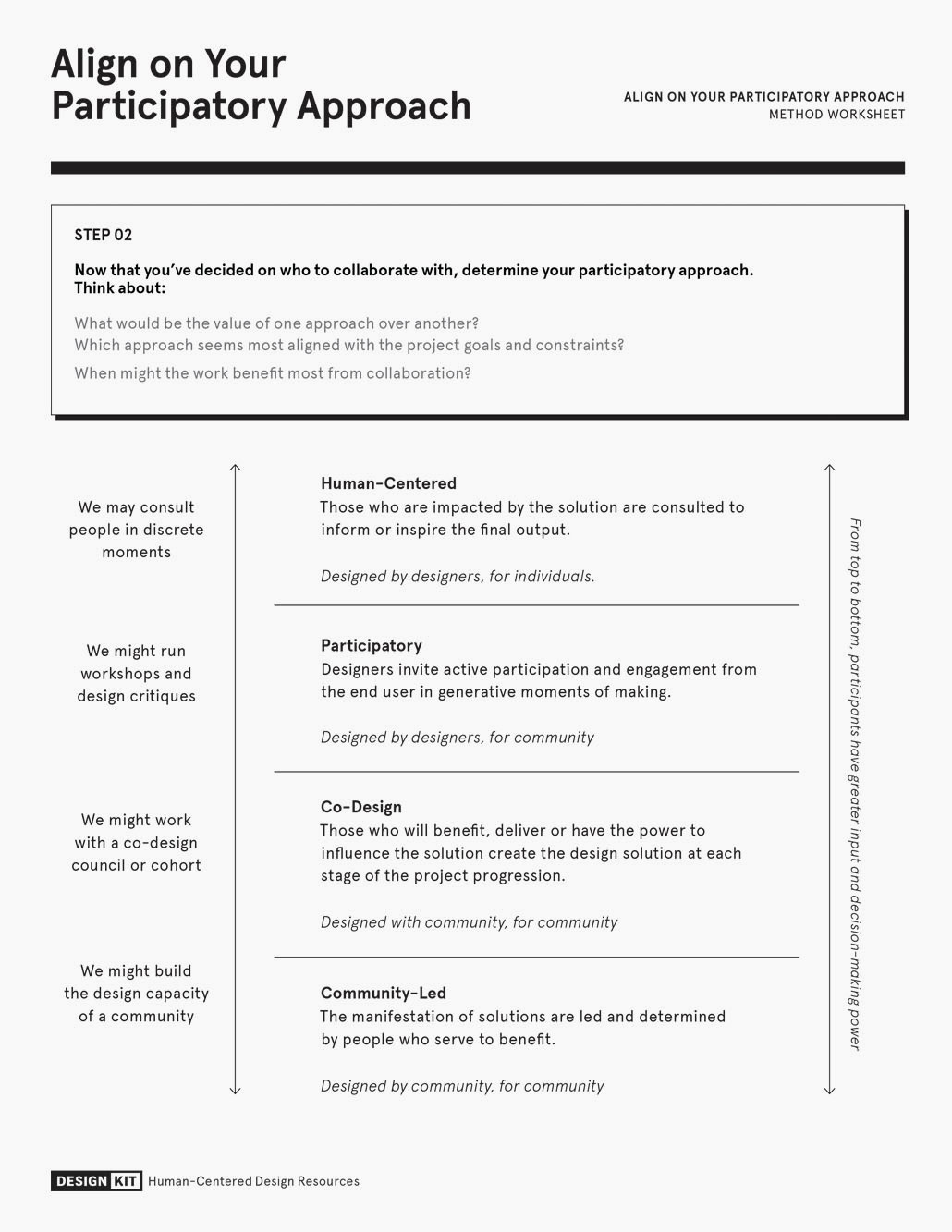

Gabriela Arboleda discusses the issue of participation within social design. “Why might participation not make much difference in the outcome of a social design project? The reason is that participation can be very easily manipulated and co-opted to carry out business as usual” (Arboleda 2020). Arboleda identifies six different ways that participation is controlled: some of these are “participation as labour” participation becomes unpaid labour for the participant, “participation as information provision” community input becomes mere content creation/information for the designer. “Deceptive participation” the illusion of participation can also be deceptive, and might include misleading the participant or manipulating them into a contribution that fits the project. “Anodyne participation” is also prevalent where involvement is trivial or incredibly undiscerning so that any form filled in, or meeting attended is used as evidence of community engagement (Arboleda 2020). Many of the methods employed within social design were borrowed from the social sciences yet the ethical considerations that go along with the implementation of these methods has not been critiqued with the same rigour as within the social sciences themselves. An excellent example of this type of scrutiny is in Poverty Knowledge (2001) by Alice O’Connor where the author charts the study of poverty, outlining the difficulties of translating academic frameworks into lived practice. She discusses how participatory research models are often tokenistic and rather become another form of external control.

Frame innovation (2015) by Kees Dorst was offered up as a new way to challenge the original design problem approach, framing was seen to expand the scope of how design problems were defined. Dorst proposed framing as a solution to tackling a radically new species of problem, “problems that are so open, complex, dynamic, and networked that they seem impervious to solution”. The principles were; to attack the context, suspend judgement, embrace complexity, zoom out, expand and concentrate, search for patterns, deepen themes, sharpen the frames, be prepared, create the moment and follow through. Similarly to design thinking, design framing has come under increased criticism. In On The Politics of Design Framing Practices (2022) Sharon Prendeville, Dr Pandora Syperek and Laura Santamaria propose framing as political acts not merely as tools for design practice. Frames, “express normative understandings until challenged”. The authors draw attention to the influence that social position, wealth and class can have on how design problems are framed. Drawing on social movement scholars' work, on collective action frames they propose an alternative “counter framing design”. They propose that future work is warranted on the “politics of epistemology that underpin frame theory”, and draw attention to its roots as predominantly white, male, Western scholarship.

There are many communities of practice within the social design sphere, some of which are more closely aligned with 'critical design’. A notable example is Yellow Spot (a portable protest toilet for women) by Elisa Otañez (2018). Rather than be driven by market logic, Otañez established through field research that there were many free urinals in cities in The Netherlands to reduce men urinating in the street, but only one public pay toilet for women. Otañez designed Yellow Spot, a portable bright yellow frame made from yellow painted steel with yellow canvas for privacy. It contains a seatless, waterless, toilet designed for hovering rather than sitting, Otañez discovered that 61% of women don’t sit on public toilets. The walls say “free toilet” in black lettering with facts about public toilets available for women printed on the inside. Like many critical-design interventions, Yellow Spot raises awareness through disruption rather than forging institutional partnerships. Otañez identifies the lack of public toilets for women as a form of discrimination in public space. is at its core a piece of public design intervention.

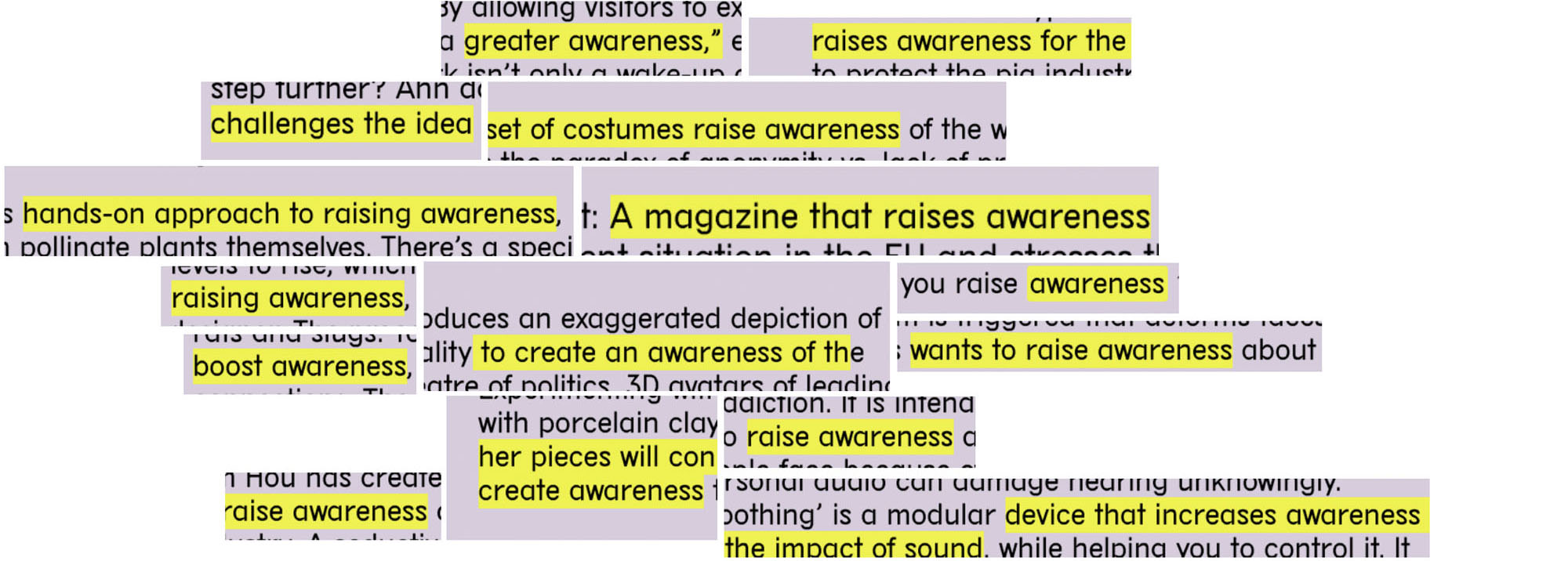

There are tensions within design discourse about the value of making people aware of issues. Afonso Matos’ piece Awareness (2022) is a collage of graduate project descriptions that contain the word ‘awareness’ — a simple portrayal of the over saturation of the term in design education. The information deficit model, a term used in the 1980s, described how the public's skepticism about science and new technology was supposedly rooted in a lack of knowledge — and that if the public only knew more, they would be more likely to embrace scientific information. Yet research showed that people who are simply given more information are unlikely to change their beliefs or behaviour.

Having said that, a more critical lens to public problems is welcomed and there are a host of contemporary social designers moving away from traditional approaches and instead foregrounding political and ethical practice and emphasising material or embodied approaches. Designers like Femke Hoppenbrouwer explore ways to remediate aesthetics to jolt us out of previously held stigmas, while Gabriel Fontana uses sport and pedagogy working with PE teachers in schools to encourage students to resist social power structures and body norms. Fontana’s games encourage school children to negotiate, resist and rearrange existing social hierarchies.

Looking to the future of social design, Jonas Voigt proposes “post-social design” and suggests that the notion of social design and human-centered design needs a complete overhaul. Post-social design advocates for inclusivity of non-human entities and acknowledges the interconnectedness of human-beings and nature in design discourse. Post-social design has affinities with post-human centred design or more-than-human centred design, where the human is decentered, instead asserting the role of non-humans in the design process. How might educators navigate this changing landscape, does post-human centered design fit with the notion of being ‘industry ready’.

At a recent imperfect index panel talk in Bristol (organised by Abbie Vickress and Laura Parke), Kaiya Waerea spoke about a certain idea of ‘professionalism’ within graphic design that becomes prohibitive. Some students struggle with knowing how to articulate themselves within the current shape of professional practice. From an educators perspective this comes down to the jobs available and the ways in which local studios shape landscapes of employment. Paul Souellis talked about understanding how students need to enter certain facets of the graphic design industry to “follow the money” and “pay down debt”.

While the panel did not discuss post-human centred design or social design specifically, they discussed the importance of creating niche communities and alternative spaces for students to go within or outside the design industry. So whilst teaching design methods that de-centre the human and engage the non-human is exciting and important, the difficulties come when educators are faced with thinking about graduate outcomes and how to translate this type of design scholarship into careers for students. For students passionate about de-centring the human within social design or designers who are critical of neo-liberal design approaches, accumulating examples of researchers and designers who have carved out alternative ways of creating work might help them navigate a different design industry around the periphery of industry norms.

Frameworks and Articles

IDEO Design Kit: The human-centered design Toolkit

Arden Stern and Sami Siegelbaum: Design and Neoliberalism

DESIS: Network for Social Innovation and Sustainability

Gabriel Arboleda: Beyond Participation Rethinking Social Design

Robyn Cook: Design Thinking, neoliberalism, and the trivialisation of social change in higher education

Sharon Prendeville, Pandora Syperek, Laura Santamaria: On the politics of design framing practices

Tracy Smith-Carrier: Charity isn’t just or Always Charitable:

Exploring Charitable and Justice models of Social Support

Books

Afonso Matos: Who can afford to be critical

Alice O Connor: Poverty Knowledge: Social Science, Social History

Elizabeth Resnick: The Social Design Reader

Ron Wakkary: Things we Could Design For More Than Human- Centered Worlds

Social Matter, Social Design: For good or bad all design is social

Case Studies and Practice

Civic Square: Neighbourhood Doughnut

Elizabeth Ottaniez: Yellow Spot Toilet project

Femke Hoppenbrouwer: Het Scootmobiel Dans Collectief

Tim Brown and Jocelyn White: Design Thinking for Social Innovation

List of Figures

Cover: Yellow Spot, Otanez, E. (2018). Photograph by Elisa Otanez.

Figure 1: IDEO Design Thinking Process https://www.ideou.com/en-gb/blogs/inspiration/design-thinking-process?srsltid=AfmBOoo8RScxY-HwlCUMViakfUSsVsslIEfpCivufm-vcz0QiKCptNgy

Figure 2: Strategyzer: The Business Model Canvas featured in the IDEO Design Kit. https://www.designkit.org/

Figure 3: Align on your Participatory Approach Worksheet IDEO Design Kit https://www.designkit.org/

Figure 4: Yellow Spot, Otanez, E. (2018). Photograph by Iris Rijskamp

Figure 5: Yellow Spot, Otanez, E. (2018). Photograph by Elisa Otanez.

Figure 6: Awareness, Matos. A (2022). A collage of graduate project descriptions from Design Academy Eindhoven.

Figure 7: Multiform Fontana, G. (2018).

Figure 8: Imperfect Index panel (2024) Photograph by Ruby Turner