We sat down in Temple Bar Gallery + Studios with David Joyce, founder of Language, and Clio Meldon, designer at Language, to find out more about the studio, its culture and the work produced, with a particular focus on the identities Clio and her colleagues made for Yes Equality (2015) and Together for Yes (2018). Watch the video clip or read the full interview below...

Tell us a little bit about Language: when was the studio founded and what does it do?

David:

Language is 30 years old, founded in 1989. I think the studio grew up initially as a graphic design studio providing services for not-for-profit organisations, voluntary sector organisations and so on. Over the course of the working life of the studio we worked with education clients and public sector clients and we have moved into advertising and campaigning as well as graphic design because the client structure fluctuates.

But the backbone of it has always been membership organisations which could be public sector, voluntary sector or NGOs and even now we work with the Irish Human Rights Equality Commission, we work with Solas, we work with the Further Education and Training Authority, we work with Temple Bar Gallery + Studios, we work with Firestation Art Studios, we work with many different arts organisations, with the Daughters of Charity. The way things work in Dublin, in our experience, is that work makes work. And if you have a reputation for a particular kind of work then that leads to other work. Because we kinda grew up in the not-for-profit, voluntary sector space, I think we are seen as experts in that area.

In addition, you do a lot of socially engaged work, was that strategic or did it evolve over time as you describe, work leading to work?

David:

I think it was a bit of both. I think the studio was set up to do that. I think even when it was initially set up it was to help organisations communicate for themselves, on behalf of themselves, and I think that idea has worked all the way through Language’s working life, and possibly, you could say has culminated in the Yes Equality, and Together for Yes referenda.

You briefly touched on the work you did for Temple Bar Gallery + Studios, which opened back in 1983 when much of Dublin was laying vacant – so Temple Bar itself and Dublin has seen drastic changes in that time. Do you think social change has influenced the cultural approach of this organisation?

David:

We started working with Temple Bar Gallery + Studios (TBG+S) about 20 years ago, and Temple Bar Gallery + Studios was one of the first membership organisations to actually manage to find a place in Temple Bar where a collective of artists could get together, organise themselves and create studio spaces at affordable prices, where they could make work.

At the time, in 1983, Temple Bar was probably just literally on its upward curve, from being derelict to having some money poured into it, all that kinda stuff. It was an amazing thing to do at the time because it could very easily have moved into a commercial space. The crux of it, from a social point of view, was to accommodate and facilitate artwork being made in the centre of the city, in a collective way that was very DIY actually, very punk in many ways, I remember talking to Rayne and Clare 20 years ago, about this idea of putting an identity together for Temple Bar Galleries + Studios, because they had a logo but didn't really have any system in place.

We talked about this idea of a DIY approach, that I could help them set up the components or the toolkit if you like, for them to make their own communication work and that could be signage, memos, website, anything. So I worked with them to set up the parameters of that and then pulled away, and left them at it and they went to town, and you know, it’s still working now so it’s obviously been reasonably robust. But I think that collective energy has been really important for them, where they take ownership of the space, ownership over what it is they say about the space, in how they attract artists into the space.

You've also worked directly on projects where art intersects with social issues and politics such as Art and Activism, a World to Win and Women to Blame. Tell me a little about what prompted Women to Blame?

Clio:

Women to Blame was an exhibition that chronicled 40 years of struggle by women in Ireland for contraception and reproductive rights. The clients came to us with an incredible archive of primary source material going back to the ‘60s and ’70s of flyers, posters, memos, notes, handwritten pieces of work chronicling that entire struggle, so from a trade union point of view and from a personal point of view we had these amazing resources that were in really good order, that were really well organised. It was my job to put a graphic shape on that and to let the art and design of that shine through, to tell a story of how things have changed but also at that point in time they really hadn't changed (it was 2014). We had made a lot of leaps socially but there was still the 8th amendment at the time and women didn't feel that they had reached the point of equality when it came to reproductive rights.

So we divided up by decade and intersected that with the waves of feminism to tell a really rich, really interesting story. For me, so much of it happened before I was born, and was almost kind of folklore but to be able to hold artefacts in my hand and read first-person accounts of what life was like was absolutely fascinating. It was the very first project I worked on in Language so I was totally thrown in the deep end as an intern working on this massive project dealing directly with the clients, presenting and figuring out how to physically make it work but it was a total dream come true straight out of college.

David:

What Clio was talking about in the Woman to Blame project, it was almost curatorial, there are artefacts in place, there are documents that have been identified that need to be showcased and communicated in an exhibition.

We worked on a book that’s in the 100 Archive as well for TBG+S called Generation, a collection of archival material going back from 1983 up to 2013 at the time, but it was everything from legal documents to planning permission for things, the architects’ notes etc. So those artefacts, from a graphic design point of view, our approach was more conversational, trying to use a kind of modest graphic content to tell the story. Both of those projects were effectively collage — it was about the holistic approach, not focusing on one particular thing, but rather how everything works together.

In terms of art and social, is there anything, in particular, you want to share?

David:

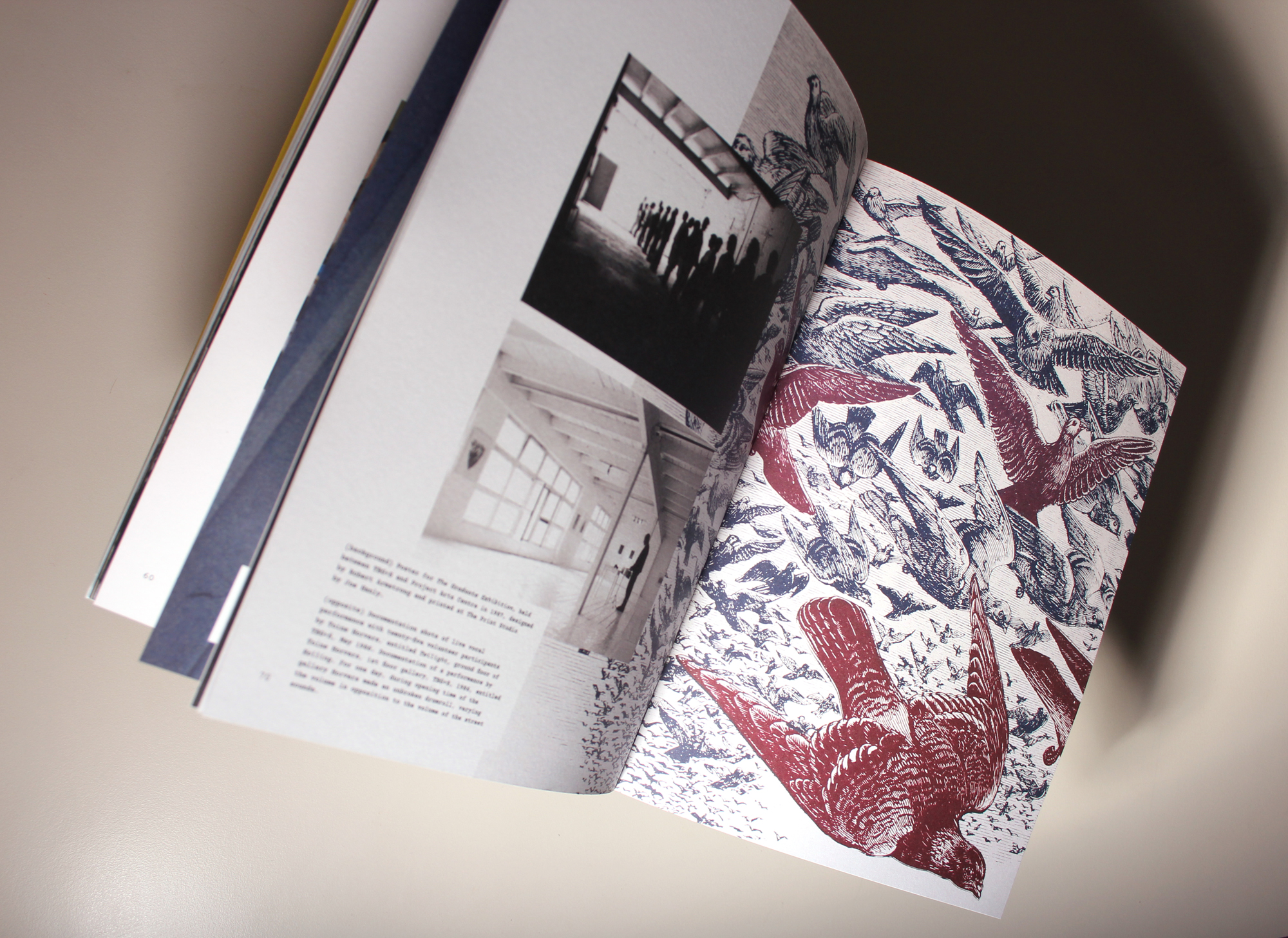

I'll talk a little about Art & Activism, a book that we worked on for Fire Station Studios, another organisation that we've worked with for many, many years. They are based over on Buckingham Street, they have a local youth group in their space, they are funded by Dublin City Council. They run residential studio spaces for artists that you can apply for at a very low rent and they have sculpture workshops. But I think at the core of their practice is the social connection with the outside, with people. So it’s not that art is in a bubble, that it’s highfalutin’; rather it is that it’s grassroots, community-based, public. They are very interested in the idea of public art and the Art & Activism publication that we made for them was in response to seven artists that collaborated on a project called Think Tank and it included artists and curators from here and abroad exploring what activism means through artistic practice today.

If we look at the starting point of the 100 Archive, it’s 2010, the country is in the grips of recession, and some of your more grassroots or political works deals with how the recession impacted on real people. So Jobs not Debt, Fair Shop, Decent Work, Make Rights Real...

Clio:

There’s a whole gang of people in the middle that it really hit, like if you’re coming out of college then its really hard to catch up, you're lost. I finished college in 2014, and things were lifting a little, but there was still that kind of hangover from the recession. Going to art college, people were like, “What are you doing?! Where are you going to work?!” I ran into my art teacher from secondary school a couple of months ago, and she asked me “You're working?” – Yeah, as a graphic designer, “Full time?!”

As for my contemporaries, not everyone has stayed in the industry, but anyone that has is doing pretty well, I think... they’re working and they’re happy. Some people have gone abroad, some people had done masters, and some people have completely gone the other directions, become teachers for example.

David:

The Jobs not Debt project was orchestrated by the Irish Congress of Trade Unions, who we've worked with for many years. What was interesting about it was it was a kind of culmination of a lot of our clients, because the ICTU would be a membership organisation for membership organisations, a union for unions. We worked with PCEU, CPSU, CWU and Mandate, who is someone we worked really closely with over the years. We were asked to illustrate that notice of €64 billion debt, which would culminate in a march that happened in 2012, possibly 2013, which was one of the biggest marches in Dublin city ever.

They had a logo which was kind of like people lifting up this massive dumbbell. We were talking about it in the studio and we decided that what would be amazing would be to physically make this dumbbell, 30 ft high, 30 ft wide and get actors to pull it along, physically illustrating what that burden was. That became the beginning of the actual parade, which went back for miles, and miles...

It got a lot of coverage, and it really helped to communicate to people in a really basic way what we had been lumbered with, and what we have to deal with, and what we still have to deal with. And what’s amazing is I don't think people fully understand that’s still knocking around — individually we still have thousands and thousands of euros of debt that not only we will have to pay back, but our kids will have to pay back, and presumably or kid’s kids will have to pay back. So it was a really important statement that the clients wanted to make and we were really engaged as a studio trying to make that happen.

Decent Work happened around the same time as the Jobs not Debt march and involved Mandate trade union, who represent bar and retail workers who deal with precarious work in an ongoing way – zero-hour contracts, people who don't know one week if they are going to have a job the next, employers who don't engage with collective bargaining, pretty dubious contractual arrangements and so on. They wanted to showcase the impact austerity was having on people in low-paid jobs, to lobby and fight for decency at work, which includes an increase in the minimum wage and which tries to encourage employers to agree to collective bargaining on behalf of workers. We made this banner for the outside of their space up on Cavendish Row on Parnell Square along with a bunch of communications materials, booklets, reports etc that carried that identity through.

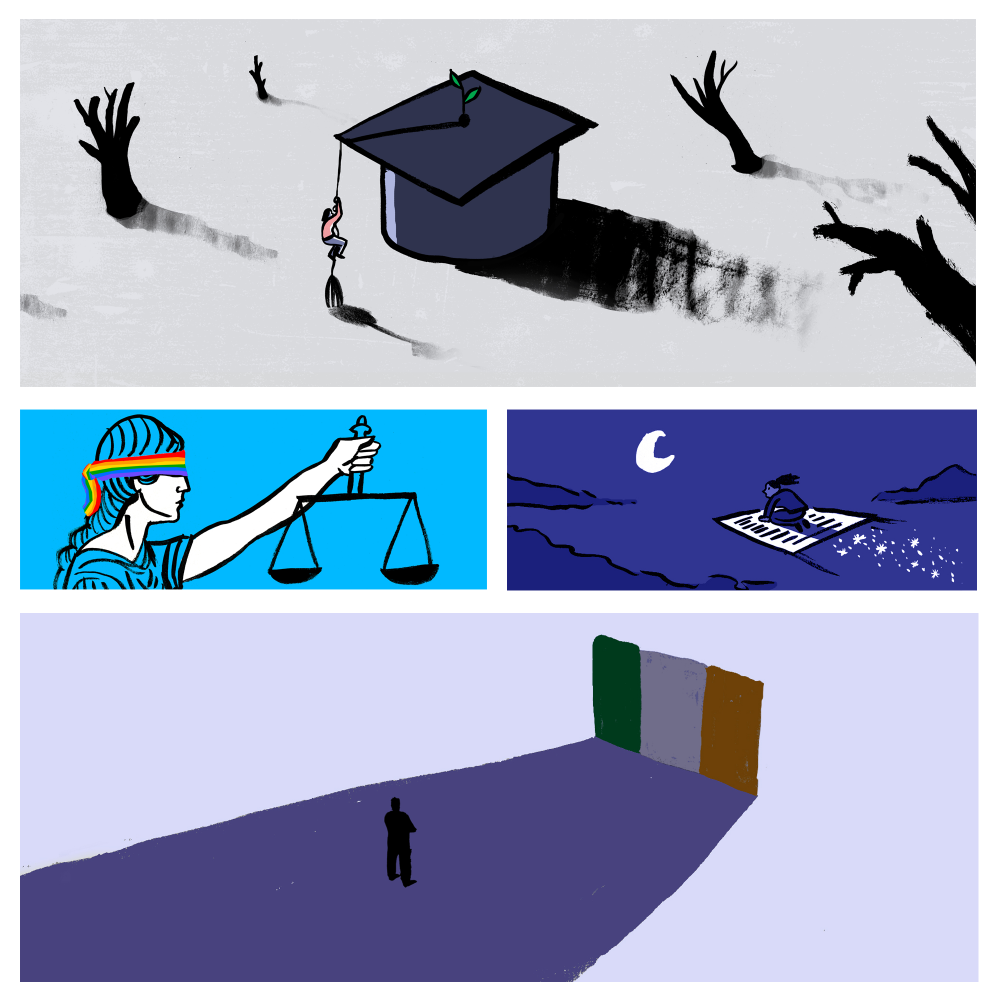

Make Rights Real was a project for the Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission, and that was a campaign about human rights, to make people aware what their basic human rights were, not everyone knows what their human rights are… it’s complex. So we came at it from an editorial point of view and made a website that pulled in editorial content and visual content to help people understand what their rights were.

So you've already dealt a little with how the client structure changes a little over time, from the start of the Archive to now, and bearing in mind some of those social issues we discussed, what changes as a studio have you noticed?

Clio:

Before I started the studio had bigger, higher-end clients like Lexus. I think we’ve come back to our roots, to public interest campaigns and so on.

David:

Business is business: you diversify and you try new things and you try to move the studio in certain ways. People come into the studio with certain expertise and therefore that becomes the profile, and you're right, at one point we were working for commercial clients. Now the studio is smaller — I think back in 2010-2012 in response to the recession the studio reduced in size, and it hasn't really gone up in size since, there’s about 10 of us. And yes, I think we are concentrating, I think the work is quite similar to when we started, and that journey has kind of culminated in Yes Equality and Together for Yes, which had their roots 25 to 30 years ago, and only came to fruition recently.

In 2015 Ireland became the first country in the world to introduce marriage equality by popular vote, and you created the Yes Equality identity and strategy. Tell us more about that.

David:

Yes Equality is an interesting project if you think about it in relation to what we've been talking about and some of the previous projects and some of the previous relationships and conversations going back a long time, going back 20, 30 years. All of this informed the Yes Equality project. The relationships that were there for many years, working on various different projects with different outcomes came together under this umbrella, which was essentially about a collective energy.

It was a collective energy within the studio, the whole studio was involved in the process of making the identity, and similar to other projects we've worked on and the way we approach identity design it was not only about people in the studio working on it but also this idea of handing it over to people outside to run with it.

And that was the amazing thing about that campaign, we have photographs of people making their own posters, people crocheting things, knitting things, you know, you've got Carlow Yes Equality, from all over the country, from all over the world, it seemed to capture the energy of it, and again, similar to the DIY thing I was talking about with TBG+S there was a kind of a DIY-ness about it, and the way the identity system was set up it was malleable. It wasn't set up in a graphic design-y way, rather it could be used by anybody. It was set up in a way where it had fundamental building blocks, it had a system in place whereby someone could take it and make something themselves from it. We do that all the time, we have done it for years and years and years, and I think that approach culminated in that project in many ways. People took it on and ran with it.

Were there any examples where you saw the identity used where you were raging that you didn't think of it yourself?

David:

I think there was no one piece that sticks out for me, we’re not precious about stuff like that, like, if somebody paints it on the back of a bus or makes a t-shirt out of it or spells it wrong, or uses the wrong colours or whatever, I kinda feel that’s part of it. There’s a real energy to that. What was really amazing was that people themselves felt ownership over it, not only of it as a campaign, an idea, but that they could graphically make things themselves. It was remarkable.

I want to move onto Together for Yes which I think again had similar kind of design and advertising industry support, and a lot of people making work, but I think it was a slightly less comfortable issue society-wide. The subject matter was just that little bit more sensitive. I know there’s a hugely collaborative nature to a lot of the projects we discussed today: Together for Yes is an umbrella organisation made up of over 70 organisations, and they worked to successfully repeal the 8th Amendment. Again, you created this national identity and strategy: how did that work?

Clio:

Together for Yes came about very similarly to Yes Equality in that we had relationships with members of the organisations beforehand. Our colleague Adam May worked to help build the coalition between the three main member groups: the Abortion Rights Campaign, National Woman's Council for Ireland and Repeal the 8th.

While it was a huge umbrella, there was quite a small team of decision-makers and they were very interesting to work with. They were very democratic, they all had to agree, they discussed which way things would go and I'm sure behind closed doors there were difficult conversations had. But when it came to decisions on my level as a designer it was very straightforward: yes, no, change this, do this… There was a very short amount of time between the announcement of the date of the referendum and the beginning of the campaign so it came around really fast, but there were a lot of very decisive people who knew what was coming. Their strategy was really solid, they knew what they were saying and why they were saying it. It made our jobs, I won't say easy, but definitely easier.

So at this point, you're out of college 3/4 years and you're all of a sudden involved on a national level with a hugely socially important project. How did you approach the project, and what did it feel like on the 26th of May, when you hear the percentages returned?

Clio:

To be involved with Together For Yes was almost indescribable. As a young woman, a mother, a person in Ireland, having grown up with one way of life and being on the cusp of everything changing and being a part of the team that helped make that change was unbelievable. In terms of discussing with people, it made some conversations easier because I was so involved in it and believed in it. I'm working on this because… yes, it’s my job, but also I'm so thankful it’s my job. I have the privilege to be involved in a campaign like no other.

It was definitely tough at times, but I think the closer and closer we got to the date, people felt braver, people felt more able to talk, able to share, and the Together for Yes badges were a huge boost to public discourse and public perception. I mean you'd walk down the road and every other person had a badge. I made that badge, that’s so cool! Not just that I made a badge, but everyone’s wearing it and they are wearing it because they believe in this. I mean it was incredible, two people got it tattooed on them after the result and that blew my mind!

Do you have any thoughts on the power of design in the context of social change? These are two huge examples, alongside all the others, as you say, you're walking around in your day to day life and you’re encountering people who are emblazoned with this work you've put together...How crucial do you think design was to those yes votes?

Clio:

I think there is something important about the design structure that Dave spoke about for Yes Equality, that it was created to be shared and to be taken on by the individual and to be their emblem, their design, their badge of honour. I think that, yes, graphic design can be really powerful, but it’s only as powerful as the people behind it and the collective conversation and the belief that Ireland was ready for change to be made. It was incredible to be able to design the visual heart of that but the people were the real heart of it, the stories, the Facebook posts, the conversations, no matter how awkward or difficult. It was not about the design, that just gave someone a badge to wear, it was the stories that changed minds.

David:

Yeah, it's an interesting one because sometimes I feel that graphic design is about discourse, and discourse can mean, “This is what I think and you should listen to me because I know what I think.” While what we're interested in is more about dialogue and conversation, and I think Yes Equality and Together For Yes were good examples of design as dialogue, or design as conversation, where it's not highfalutin' or high brow, it’s not about this massive burdening aesthetic, it’s about making it useable for people, and when people are happy to use it and they love it, they go with it.

So what’s next?

Clio:

I think the change in both of those instances came from the people, came from society. So, what else is out there, it’s not necessarily what are we going to change next, it’s what can we help change.

Are there any kind of buzzwords you’re noticing more from clients? Is it immigration, sustainability, is it the environment?

David:

I think the environment and climate change, I think there are lots of conversations around that, lots of fear about it. I mean my kids are fearful. I have a 15-year-old son and, with the stuff going on in Brazil and so on, he's freaking out about that, so climate change, sustainability, green issues are vast and hugely problematic... I would imagine that that would start coming into people’s thinking more and more, where people will consider outputs, consider what they are actually physically making themselves, which will inform directly what we do.

There’s an interesting thing about it, where people choose not to print, or a report is going to have a digital presence instead of a print presence, but I'm not sure I fully understand what the impact of that is. You've got these massive servers around the place pumping out all this stuff, I would love to know what the implications are for printing 70 reports for an organisation versus keeping something online for 2 years, you know from a sustainability point of view. I think we need to start thinking more holistically about it, there’s a real knee jerk reaction, but I'm not sure people are fully thinking about it.

So it’s more about social engagement?

David:

It’s absolutely more social engagement. It’s about having conversations, it’s about talking to people, about seeing what we can do.

____

This article is part of a research project called Map Irish Design, undertaken by the 100 Archive and funded by the Creative Ireland Programme. The project explores how design affects life, culture, business and society in Ireland, as viewed through the communication design work gathered by the 100 Archive since 2010. See the project at map.100archive.com