Did you know…? Thirty-nine percent of the work submitted to 100 Archive is commissioned by the cultural sector. Our community is reliant upon the health of that sector, ensuring that it is adequately funded, as well as effectively and ethically managed. Within an Irish context, the only movement for creative workers' rights comes from the arts and culture sphere, notably the National Campaign for the Arts and lobbying work by Theatre Forum. In the UK, the newly-established Designers + Cultural Workers Union is making bold steps to unite workers in these sectors to organise for their collective rights. The group evolved out of research into problematic working conditions in the graphic design industry, some of which are specific to workers in the UK, and others that might resonate with design practitioners within a broader global context. You can find out more about this cross-sector trade union here.

Following on from our recent Viewpoints on the 4-day working week, we asked the DCW to contribute a piece of writing to the evolving discussion about creative workers’ rights on 100 Archive.

____

Cultural Sector Timelapse

‘Free labor and rampant exploitation are the invisible dark matter that keeps the cultural sector going.’ – Hito Steyerl

Preamble – ‘No longer invisible!’

Our union’s rallying cry, ‘No longer invisible!’, articulates the alienation experienced by the most precarious workers in society. It seems a fitting slogan for our current epoch-defining moment. Like an x-ray to our body politic, coronavirus illuminates (and reclassifies) previously ignored workers, and exposes the structural discrimination they experience.

When approached by 100 Archive, we thought that a timeline of events since COVID-19 would make ‘the argument for establishing a union for design and cultural workers’ better than any article could. However, soon after we attempted this chronology, we realised our sector was in crisis long before this pandemic.

Instead we offer an irregular timeline of events/reflections[1]; exploring the relationship between time and labour, and our own recent branch activity (@)[2]. (Dis)ordering this article into micro-chapters offered some architecture for plurality, echoing how we advocate for a more complex understanding of our cultural sector – looking behind what is only visible.

Living History

B.C. can now mean Before COVID-19 [3], with A.C. describing both the present and speculating on the pandemics conclusion [4]. Continuance is humdrum and horrific – ‘how much longer?...’ narrates a child's stay-at-home lethargy, and the grim wait of a frontline worker for personal protective equipment.

Time Warp

The current crisis warps our individual and collective sense of time. The pandemic pendulum oscillates between preparation (B.C.) [5], and mitigation (A.C.), a time machine of sorts. The UK is 2 weeks behind Italy; tick, the UK had since January to prepare; tock. As cultural workers, our clocks are set to the government’s own timetable of various fiscal support. 5 weeks wait for Universal Credit; tick, 3 months until the self-employment Income Support Scheme; tock [6].

The Clock King was one of Batman's many colourful adversaries. He had no superpower but proved a formidable opponent nonetheless, using time for crime – from an exploding pocket watch to his precision in a fight, knowing the best moment to land a punch.

Time Spent

Mechanised, mathematical time-keeping facilitates the exploitation of workers by transmuting ‘time from a process of nature into a commodity that can be measured and bought and sold like soap or sultanas’[7].

The current economic orthodoxy is predicated on time-saving infrastructure, just-in-time production [8], and time spent consuming – synchronised through unscrupulous time-keeping [9]. Put another way, late-capitalism makes life appear/operate velocious(ly), generating a sort of time-lapse; where things appear to be moving faster and faster, thus lapsing.

During an escapade aboard Captain Hook’s ship, Tick-Tock Croc accidentally swallows an alarm clock, gaining his nickname and a constant ticking that acts as something of a warning. Chronophobia is a specific psychological phobia which manifests itself as a persistent, abnormal and unwarranted fear of time or of the passing of time.

Beat The Clock

As cultural workers, we are continually against the clock. Scrambling to meet unrealistic deadlines by working unpaid overtime (@), applying for funding, chasing clients to pay late invoices, switching between a second (third, fourth) job [10], and so on (ad infinitum). We are rarely salaried, instead working on zero-hour (or non-existent) contracts, paid in hours or days, or half days, or for specific calendar periods [11]. Our activity and personal development must be constantly time-stamped (with zeal) through social media and portfolio sites [12].

While most workers struggle to keep up, our industry celebrates its own toxic tempo; from apps that accelerate production, like onuniverse (How to make a website in 3 seconds). To blogs like It’s Nice That, who celebrate high-speed projects (How the video for Fenn Rosenthal's Dinosaurs in Love was made in just 24 hours). And so-called educational programs, like Shillington, that attempt to collapse years of design learning into seemingly no time at all (Become a graphic designer in 3-months).

$10,000-a-second and the 10,000 Year Clock

Amazon’s sales and profit figures for the first three months of this year were purported to be as high as $10,000 every second – day and night.

The retailer's president, Jeff Bezos, has to-date invested $42 million to support the construction of a giant mechanical clock that will run for 10 millennia. The Clock of the Long Now – named by musician Brian Eno [13] as a counterpoint to today’s culture of the ‘short now’ – is one of many durational projects initiated by the Long Now Foundation, aiming to foster long-term thinking.

Punchcard Economy is a project by artist Sam Meech that weaves together people’s recorded working hours from the cultural sector (including unpaid overtime). Transforming this data into a machine-knitted banner portraying Welsh textile manufacturer and utopian socialist Robert Owen’s slogan for the short-time movement. (꩜)

Short-time

Labour movements have historically opposed the tyranny of the clock king(s), from fighting for the eight hour work day, to the recent campaign for a 4-day week [14]. Regulating and fairly remunerating working time is a basic tenet of Trade Union organising.

Time-poor

To be time-poor suggests a lack of spare time. It describes an imbalance between (paid) work and leisure. It colloquially (and naively) implies that those income-rich comprise the time-poor (more hours worked = less time, but more cash).

But an expanded definition, ‘time poverty’, includes reproductive labour or unpaid work; cooking, washing, caring, resting; demonstrating the correlation between wealth and time – those that lack capital (human, financial, social) cannot afford to make time. Put crudely, to be poor is to also be time-poor.

BLACK POWER NAPS – Photography by Avi Avion. Like most resources, time is unevenly distributed. Research suggests a racial disparity to hours rested, with people of colour burdened with insufficient sleep. In response to this sleep gap, artists Acosta & Sosa curate soft spaces for slumber, facilitating downtime and inviting people of colour to slow down and refuse discriminatory exhaustion. Their work demands reparations in the form of rest, relaxation and idleness. The right to dream (literally).

Lapse

Lapse; meaning error, negligence. But also; fall, slipping, descent... gap, pause, interlude, hiatus. In late March (A.C.) a series of support packages were announced by both the Chancellor of the Exchequer and Arts Council England. What’s striking about both responses were the omissions (synonym of lapse).

The government’s initial furlough scheme was immediately criticised for excluding gig economy workers and the self-employed (@). A momentary lapse, as a week later the Self-employed Income Support Scheme was announced, but with a gap of 3 months before payment. Unsurprisingly, cultural workers often fall outside of the government's own narrow definition of worker, rendering both support schemes inaccessible [15].

Arts Council England’s Emergency Response Fund, while initially welcomed by many (ourselves included) revealed serious lapses once the full details were published. By cancelling already-in-progress applications, increasing competition for less overall funding [16],and restricting applicants to those whose artistic practice accounts for more than 50 per cent of total earnings [17], ACE not only exclude those already marginalised by our sector, but re-identify them as non-artists.

This mirrors the cultural sector's long standing issue around inequality and underrepresentation; those who already have money can enter and navigate the cultural sector with more ease. (@)

Human Rights

On March 13, Tate Modern announced that an employee had tested positive for coronavirus. Under mounting pressure from trade unions the building closed five days later. Senior staff justified the delay, asserting the employee was not front of house, and that deep cleaning Tate’s offices had neutralised the risk of outbreak. The errors of this response now seem obvious, however, it noticeably illustrates that it’s the most precarious, undervalued and underpaid workers who were more likely to be put at risk [18].

When the Tate finally shut, its closing statement reflected that ‘access to art is a universal human right.’

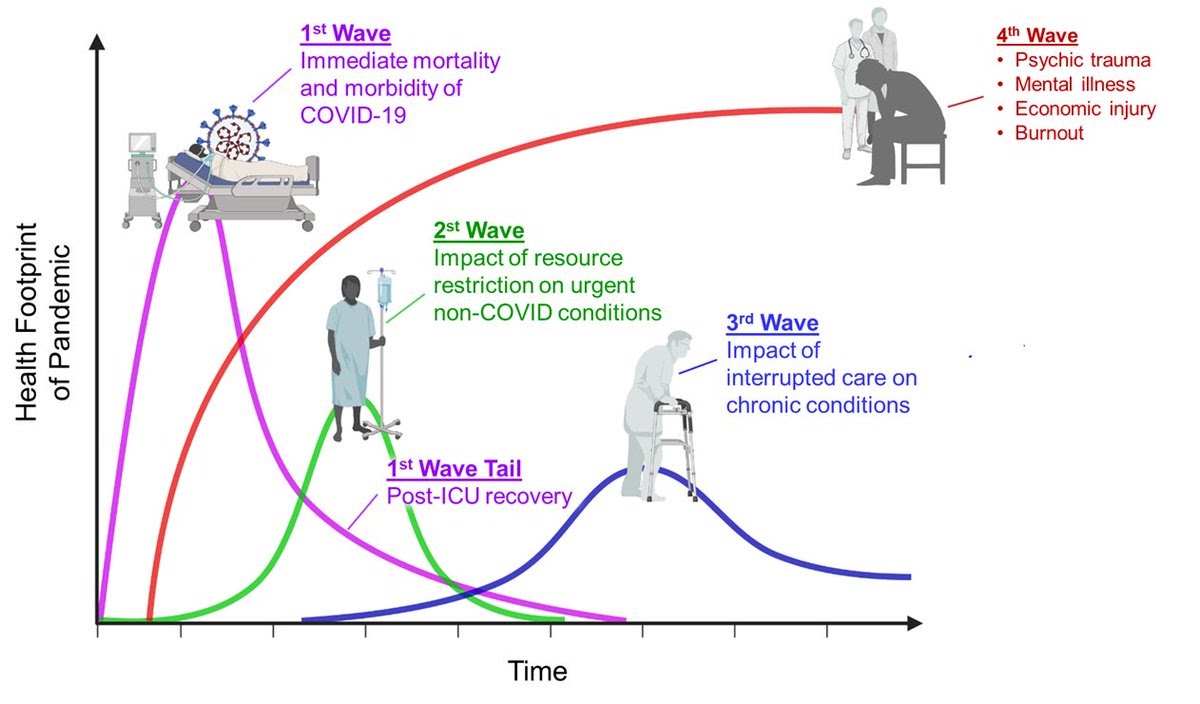

Infographic forewarning a series of covid-19 related aftershocks. Credit: Pulmonary & critical care physician-scientist Victor Tseng.

Slow Violence

On November 15, 2017 (B.C.), British Medical Journal published a peer-reviewed report linking nearly 120,000 excess deaths to the squeeze on public finances since 2010.

In November 2018 (B.C.), Philip Alston, the UN’s special rapporteur on extreme poverty published a scathing account of modern day Britain. Warning of deepening poverty, Aston accused the British government of inflicting ‘great misery’ on its citizens through ‘punitive, mean-spirited, and often callous’ austerity policies. Predicting close to 40 per cent of children will be living in poverty by 2021 (A.C.) [19].

Unions, while fire-fighting the immediate shock of coronavirus, must also prepare for a series of after-shocks; redundancies as museums reopen with social restrictions and therefore less visitors (following government’s chief medical officer Chris Whitty suggestions, it wouldn’t be wrong to assume that the cultural sector will be last to return) [20]; less commissions and funding (worsened by a second wave of austerity); continued neoliberalising of our art colleges (compounded by lockdown cost-saving online learning); increased competition (depreciating wages) and the looming mental health crisis.

The Right to Disconnect

In 2017 (B.C.), the French government introduced a series of far reaching labour reforms. Many unions protested what they saw as a relaxing of regulation around working hours [21] and hiring/firing practises. However, one policy was widely applauded. Dubbed the ‘right to disconnect’, the reform compelled companies with more than 50 workers to set out the hours when staff are not supposed to send or answer emails. It’s by no means perfect; companies each interpret the law differently, presenting an obvious loophole, not to mention disregarding small businesses [22]. But it does provide a useful framework for contemporising the conversation around the omnipresence of work.

Bruno Munari, Macchina inutile Max Bill (1933-1993). Like many of Bruno Munari’s works, his useless machines (macchina inutile) had a temporal element – form(s) changing in motion (illustrated above). At the time, Munari’s friends often laughed at his kinetic contraptions, and would repurpose them as mobiles for their children's bedrooms. Reflecting on the object's name, Munari observed; ‘They are useless because unlike other machines they do not produce goods for material consumption, they do not eliminate labour, nor do they increase capital.’

Unrest

On April 8 (A.C.) AIGA Eye on Design published I’m A Design Student—What Happens Next? offering ‘concrete advice’ for those students set to graduate into a dramatically altered creative industry. The article gathered guidance from 7 educators, but within hours of tweeting pull quotes, AIGA were pressured into amending the piece.

The since removed tweet – “Be prepared for interviewers to ask ‘what did you do during the pandemic?’ If your answer is that you played on your Xbox, or even just learned to code, you’ll be viewed poorly” – elicited immediate criticism, most likely from irked students concerned the comments could normalise unethical questioning by prospective employers.

Notably, the remaining edited article still shifts the focus onto those entering the industry, rather than those regulating it, deepening the necessity for cultural workers to be constantly productive, no matter the cost [23].

The first mechanical clocks used only one hand to tell time. Having just the one hand meant time could easily be read from a distance – one-handed clocks appeared in public squares or on places of gathering. Often inaccurate, the errors of the first clock towers could be as much as half an hour per day. Still in existence – but not used(?) – they are portals back in time, to a life less frantic.

Mobilising Slowness [24]

As trade unionists, listening is part of our political practice. No longer invisible! is vociferous; a response to silence / being silenced, but it’s also an invitation to contemplate – whose voices are missing?

In grassroots organising there is some tension between reacting to our present while fighting for our (desired) future(s), and inadvertently or not, we can all too easily embrace acceleration over sustained momentum – we burn out.

Social distancing is now solidarity, and with no picket line we must gather anew. Direct action, closeness and community require some level of reimagining, or reperforming [25]. Where possible we must make time for sustainable (i.e slow) activism, increasing our ability as organisers to perceive (lapses, injustice, ourselves, our comrades).

Postscript – Days of Future Past

What does longevity mean in the cultural sector? Too often it privileges the preservation of a body of work, over supporting the bodies of workers. In response, we must both pressure and prefigure our cultural sector – cooperative organising nurtures cooperative organisations. (@)

As many face continuing hardship, talk of change will come as little consolation. Without robust, diverse and networked cross-cultural sector labour organising (@) the chance of regressing to inequitable times past seems all too possible. But the cessation of the culture industries surely enables reformist potentiality. Now is our time to re-assemble our sector in the interests of our fellow workers, with community, equality and care at its centre. A.C. can announce a new period; As Collective.

____

Endnotes

[1] We also recommended Novara Media’s Britain And The Coronavirus: A Timeline of Failure, Led By Donkeys Timeline of failure and Art + Museum Transparency's brilliant but depressing thread tracking museum layoffs in the US.

[2] We are a circular organisation, like a clock-face, rotating roles that evolve depending on the branches actions/reactions, and using sociocracy (an equally circular organising technique) to facilitate meetings.

[3] The first confirmed cases of coronavirus in the UK were on January 29, but it wasn’t until March 3 that the government announced its coronavirus action plan, and a further few weeks until it introduced some form of lockdown (March 23). Therefore we ascribe A.C. to be this tipping point in mid-to-late March.

[4] By what measure will we define the end? As David Wallace-Wells reflects now ‘is only the end of the beginning’.

[5] The recent revelation that a cross-government pandemic drill took place in 2016 – which predicted the current burden on the NHS – was suppressed by ministers, raises fresh concerns over the UK’s lack of preparedness.

[6] ‘A quarter of self-employed people earning less than £50,000 a year do not have enough liquid assets (between themselves and any partner) to cover three months’ lost earnings, and 15% do not have enough to cover a single month.’ (IFS)

[7] The Tyranny of the Clock – George Woodcock

[8] Kim Moody, in Labor Notes, argues the crisis ‘can be labor’s “just-in-time” moment of potential power’, as it contradicts much of the commentary around employment and automation; ‘technology does not replace the human links in the chain’.

[9] Employers were quick to corrupt lockdown communication tools – Zoom et al. – into yet more micro-management and surveillance; a PanoptiCam into our private space, exacerbating unequal power relations. Comrades in UVW’s Section of Architectural Workers (SAW) have already reported members experiencing passive surveillance with ‘one worker told they must keep their webcam and microphone on at all times.’

[10] The average income derived from art practice in 2015 was £6,020 (source), forcing artists to support their practice with other work.

[11] 2020’s cultural calendar has been all but erased (Artnet and Artforum up-to-the-minute cancellation trackers)

[12] Notably, the more time an artist spends on their art practice, the greater proportion of their income this represents – allowing art income to resemble a means of financial support, in other words; a job. This creates obvious privileges for those who can afford to invest time into their practice. (Livelihoods of Visual Artists: 2016 Data Report)

[13] Eno also collaborated on the prototype for the clock’s chime, which uses an algorithm to ring a series of bells in a unique arrangement everyday for 10,000 years.

[14] It’s important to mention a 4-day week is not just about reducing the amount of time someone works, but crucially about facilitating an equal share of paid and unpaid work, including caring roles traditionally ascribed to women.

[15] Cultural workers are often both self-employed and employed, working on short term contracts for cultural sites, events or art schools, and topping up their salary with self-employed project work. This mixture of PAYE work and invoiced income prevents access to financial aid; if the majority of your income isn’t from your self-employment you're ineligible for the self-employed grant. And if you lack a fixed term contract, your employer can’t, or won’t, furlough you.

[16] As Keep It Complex detail; The £20 million Emergency Response Package actually cuts £10.4 million from the “normal” spend on grants to individual creatives. (source). Their advice on forming solidarity syndicates, to cooperatively apply and share ACE funding, brilliantly refuses the cultural sectors affinity for competition.

[17] This seems the most bizarre and discriminatory prerequisite, research suggests (see footnote 10; Livelihoods of Visual Artists) most artists do not make even close to half of their total income from artistic practice.

[18] Cleaning staff are overwhelmingly migrant, BAME workers. Death rate among black and Asian Brits is more than 2.5 times higher than that of the white population. (Source)

[19] The number of children having to rely on food banks has more than doubled during the coronavirus pandemic. (source)

[20] It’s already becoming clear that low-paid workers will be the first sent back to work in order to restart the cultural sector; front of house ticket staff and invigilators, temporary contracted art handlers, and outsourced cleaners – all will be more at risk than curators, directors, managerial and administrative staff.

[21] At 35 hours, the French have the shortest legal working week in Europe.

[22] The majority of enterprises in the cultural sector are micro businesses (95%) – businesses that employ fewer than ten people.

[23] The recent Artangel and Freelands Foundation initiative ‘Thinking Time’, acknowledges the difficulties of producing work in this current climate, awardeding £5,000 to emerging artists to support research, reflection and ideation.

[24] This term is borrowed from a recent virtual gathering: Slowness: A conversation between Tina Campt, Saidiya Hartman, Simone Leigh, and Okwui Okpokwasili, via Danspace Project.

[25] For cultural workers (and all precarious workers) fragmentation is nothing unusual, as our industry strategically atomises it’s workforce. The new union movement acknowledges this contemporary practice, and develops new forms of networked response. The ‘zone centre’ where deliveroo riders are told to wait for pick-up info quickly became a site of workplace organising for an office-less job. As workers in lockdown connect through forums and video calls, it’s possible virtual zone centres for isolated workers galvanise a newly politicised workforce (@)

____

Join the DCW mailing list for regular updates, and see their Arena page for related content.